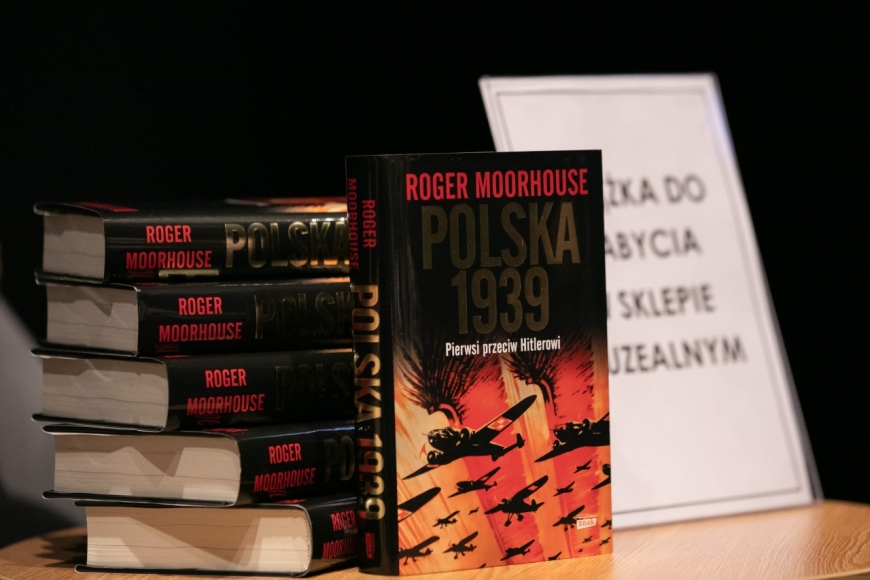

Meeting with Roger Moorhouse

On September 1st at the cinema of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, a meeting with Roger Moorhouse was held. Among other topics, the British historian spoke about his latest book, “First to Fight: The Polish War 1939”. The writer and publicist was interviewed by Grzegorz Berendt PhD, Deputy Director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk.

In his book published on August 14th “First to Fight: The Polish War 1939” Moorhouse reminds the world who was the first to oppose Hitler. The importance and meaning of Moorhouse’s work for historiography concerning World War 2 was emphasised by Karol Nawrocki PhD - Director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk:

Roger Moorhouse is a scholar who doesn’t sit around in his office in Great Britain and describe Polish history only based on documents, but conducts observational studies - as the scientific community calls it - and it is very visible in his book. This is a historian who feels Poland, understands the trail of the heroic Polish defence in September 1939, which is a great asset to his work. One of professor Moorhouse’s analyses indicates that in British historiography for each 700 hundred pages devoted to World War II, 16 pertain to the war of 1939 including international relations and the West’s reactions to the events unfolding in Poland. This shows how much still remains to be done in this context, and this work is also done by professor Moorhouse to whom I would like extend sincere thanks on behalf of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk.

During the meeting Mr Moorhouse recalled the Polish suffering in result of this most tragic armed conflict in history:

We know that one in five Poles perished during the war and Poland suffered, proportionally, the most losses. We also know that Polish borders were moved, which was accompanied by further losses, further suffering, great trauma, another wave of refugees leaving the country to settle all around the World. And to top it all off, Poland was “rewarded” with more than 40 years of Communist rule. It is therefore easy to understand why many Poles consider 1989 to be the year of their liberation and the end of World War II. If this short story was presented to any British citizen, they would be very surprised as the Polish view on World War II is practically unknown in British accounts. The British like to think themselves at the very centre of the war, when in fact they were at the periphery, with Poland remaining at the centre. My goal in writing this book was to remedy this short-sightedness.

This however, is not the only task Moorhouse has set for himself:

“My first intention was to showcase the initial weeks of the war, how it began, and its course. It was meant to inform and educate. My task - as a historian - is to study the past and to showcase it in the present. This may sound ambitiously, but my second goal was to help future historians, who are planning to write about World War II, so that they could use my book, to show Poles as something more as just the victims, a faceless mass without a voice. I wanted to tell this story in as interesting a way as possible. Additionally, I wanted to question the mythology prevalent in the West concerning the September campaign. This myth prevails where people don’t have access to information, so the average reader has no chance to learn about it and so, uses the myths present in public space. This western myth stems from the propaganda of the two invaders. One of the basic examples is the alleged fact that the Soviets never invaded Poland in 1939. Finally, my intention was to restore Polish narration to the Polish people.”

Roger Moorhouse admitted that while he worked on “First to Fight. The Polish War 1939”, he travelled Poland from one end to the other, dug through archives, spoke with historians and uncovered witness accounts in order to showcase the Polish experiences of September 1939. Although it would seem that the book is written with a western audience in mind, that is not so - Moorhouse emphasised:

“I think that the Polish reader can find a lot in this book - it includes a lot of archival materials which is largely unknown. I know that a lot was written in Poland on this subject and they are great works, however, I am convinced that every reader of my book will find something they didn’t know, witness testimonies they hadn’t seen anywhere else. Aside from that, I’m also writing from an outside perspective, I am after all British. I attempt to juxtapose the events in Poland and London at the time.”