Gustaw Herling-Grudziński | #M2WSonline

As part of the #M2WSonline project, we publish a text by Dr Tomasz Szturo, deputy director of the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk. The article describes the life and work of Gustaw Herling-Grudziński.

Epidemics, plague, pestilence... Those are the recurring motifs in the prose of Gustaw Herling-Grudziński. After all, it was he who wrote the novella, The Plague in Naples, while in his sketches and essays, he repeatedly referred to Daniel Defoe's Diary of the Year of the Plague or Albert Camus' Plague (which he considered one of the most important novels of the 20th century).

But the plague that Grudziński addresses is of a peculiar sort, it is a virus that "brought to the surface from the depths of the human soul all things that can turn man into a vile, wicked and despicable being". This virus is defined by all mutations of totalitarian systems, especially communism, which the author of the Other World called "a form of social, political and cultural plague". Its harvest were millions of victims, whom most of the so-called civilized world wants to forget. The world does not want to know.

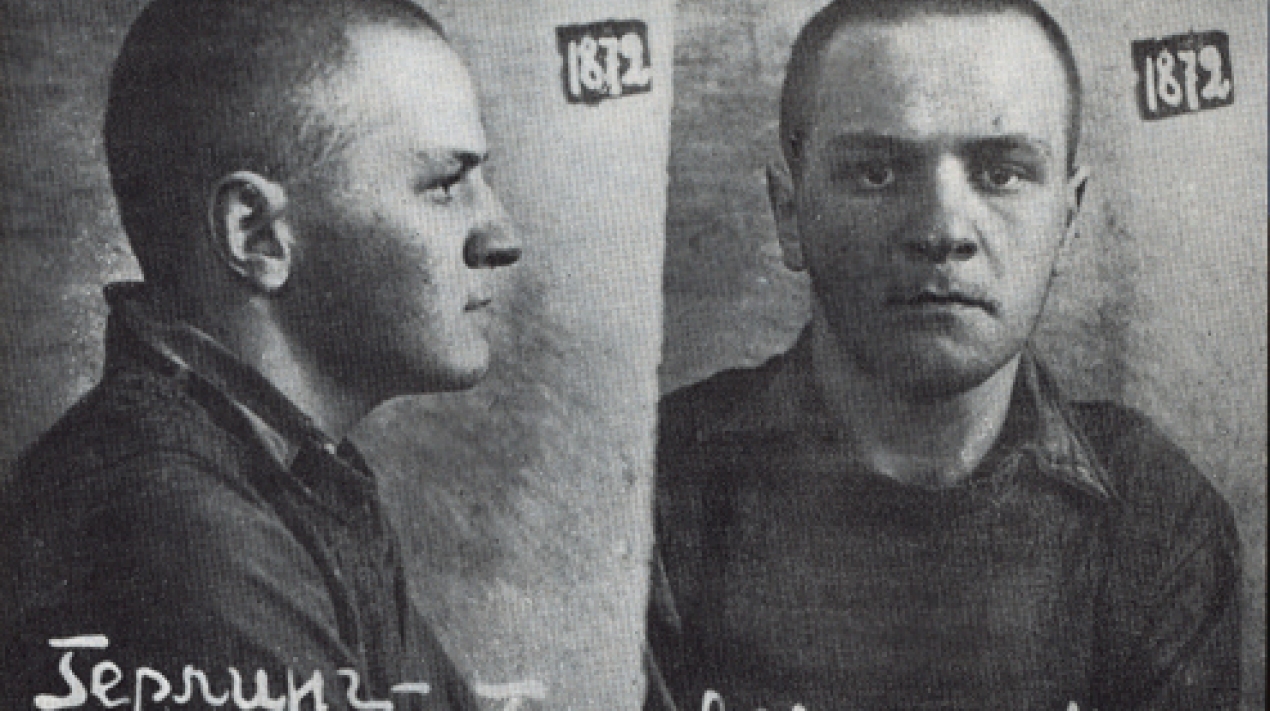

Gustaw Herling-Grudziński was born in Kielce in 1919, as Gecel Herling. He came from a family with Judaic traditions, but never flaunted his Jewishness. Grudziński respected Judaism and Jewishness, he definitely stigmatized anti-Semitism, but he chose Polishness - Polish literature, Polish culture and history. That is why he began his Polish studies, which were interrupted by the outbreak of World War II. After the defeat of September 1939, he started to engage in underground activity, co-creating the Polish People's Independence Action.

In 1940, wanting to cross Lithuania to the West (to join the Polish army), he was arrested and sent to a camp in Jercew. He left the camp in early 1942, after a dramatic hunger strike, with which he enforced on the camp authorities to obey the rulings of the Sikorski-Majski Agreement. He left the USSR with Anders' Army, and he went through the entire combat route. He fought at Monte Cassino, for which he was awarded the Order of Virtuti Militari. After the war he chose to emigrate, wandering around Western Europe (Rome, London, Munich) to finally settle in Naples, which he spoke of as the city he "chose to die in". He co-created the famous "Kultura", cooperated with "Radio Free Europe", and published in the emigration and foreign press. In 1955 Herling-Grudziński married Lidia Crocce, the daughter of the famous Italian philosopher Benedetto Crocce. It was the writer's second marriage; his first wife, Krystyna Stojanowska, commited suicide.

Undoubtedly, the turning point in Herling-Grudziński's literary career was the book A World Apart: Imprisonment in a Soviet Labor Camp During World War II. Its first edition was published in London in 1951, and the preface was written by the famous British philosopher Bertrand Russell. A World Apart is an account of the writer's imprisonment in a gulag, and at the same time the most widely read title in his literary output. This is probably also the first (not counting the short fragment in Boris Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago) literary testimony of the Gulag, written long before Alexander Solzhenitsyn's books. A World Apart, despite its novelty, had a rather complex record. In the People's Republic of Poland, it was, of course, subject to a censorship ban (its first underground edition was published only in the mid 1980s).

But also in Western Europe Grudzinski was suppressed by Sartre's leftist elites, for whom the communist utopia was more precious than the truth. In France, the book was not published until 1985 - even though Albert Camus was initially enthused by it. There were also attempts to silence its outreach and question its validity in a number of ways, including by way of obstructing its distribution.

A World Apart is not only a reliable chronicle of the Gulag. It is an unparalleled study of totalitarianism in general. It is a portrait of hell on earth under Soviet sanctions, in which the Decalogue is denounced and human value reduced to basic biology and survival instinct. Nevertheless, Grudziński does not abandon readers in hopelessness and nihilism, he refuses to accept the vision of his tormentors. He opposes his oppressors with an attitude of utter objection to evil. A World Apart features the silhouettes of prisoners who persisted in their dignity, who were able to save at least a shred of humanity in most desperate conditions.

Such a literary model will define Herling Grudziński's entire writing, which consists of hundreds of sketches, essays, short stories and novellas (including The Tower, The Second Coming, The Deep Shadow), and especially a huge series, Journal Written at Night, on which the writer worked from 1971 until his death in 2000.

Grudzinski portrayed evil, suffering, and death permeating the world. He tossed his characters into extreme, borderline circumstances - like wars, cataclysms, terrible diseases and persecution. He wrote copiously about the mechanics of evil, which he was able to discern in different ideologies, institutions of power, and regimes. All in all, his literature is a radical defiance against evil. His heroes take up a fight with evil by assuming attitudes of dignity and empathy, as long as their system of values anchors in a greater value than man - in God. Grudziński's writing is deeply metaphysical, fraught with religious tensions. It is, however, not devotional or religious. Although the writer was baptized in 1945 and his relationship with God seems to be profound, those relationships are neither easy nor smooth.

The literary setting of Grudziński's texts is mostly in Italy - medieval, modern and contemporary. The scenery, composed of papal palaces, princely castles, monasteries, cemeteries, old houses and even inquisition dungeons - picturesque. But this idyllic scenery is a mere backdrop for a deeper drama - human, historical, metaphysical. Grudziński's language is revealing, exquisite, artistically crafted, and uncompromising - just as his moral attitudes were.

In various accounts about Grudziński, reflections recur about him being a difficult, austere, categorical man, engrossed in his work. Such traits form great writers, and in Grudzinski's case we are dealing with the sum of traumas in the wake of history and personal drama. At the same time, Herling-Grudziński was a sovereign, autonomous writer. He did not yield to conformism or trends of any kind. He tirelessly adhered to the truth - often against intellectual fashions and salon dictates. His attitude is often described as "Manichaean" because in his judgments and analyses he clearly separated good from evil, truth from lie. He mercilessly stigmatized the hypocrisy of intellectuals, their pursuit of careers and splendour, for which they were willing to endorse regimes and accept disreputable political dealings. He respected the authority, but he put truth and fidelity to conscience before them, so he did not hesitate to engage into a moderate debate even with John Paul II.

He was also an art connaisseur and passionate art lover, to which he devoted a number of essays and short stories. He often referenced painting to portray dramatic tensions and diverse forms of suffering (the brilliant essay on Caravaggio, in which the story of Giordano Bruno is depicted is worth a read) .

As another Polish writer wrote about Grudziński, "he never bowed to evil". To put it another way, the entire work of Gustaw Herling-Grudziński waged a total, unending war on evil.