Maximilian Kolbe Honored in Main Exhibit of the Museum of the Second World War

The Museum of the Second World War (MSWW) in Gdańsk has introduced a new addition to its main exhibit: a drawing of Polish martyr Maximilian Kolbe, generously provided by the St. Maximilian Center in Harmęże. This change is part of the museum’s ongoing efforts to highlight Polish heroes.

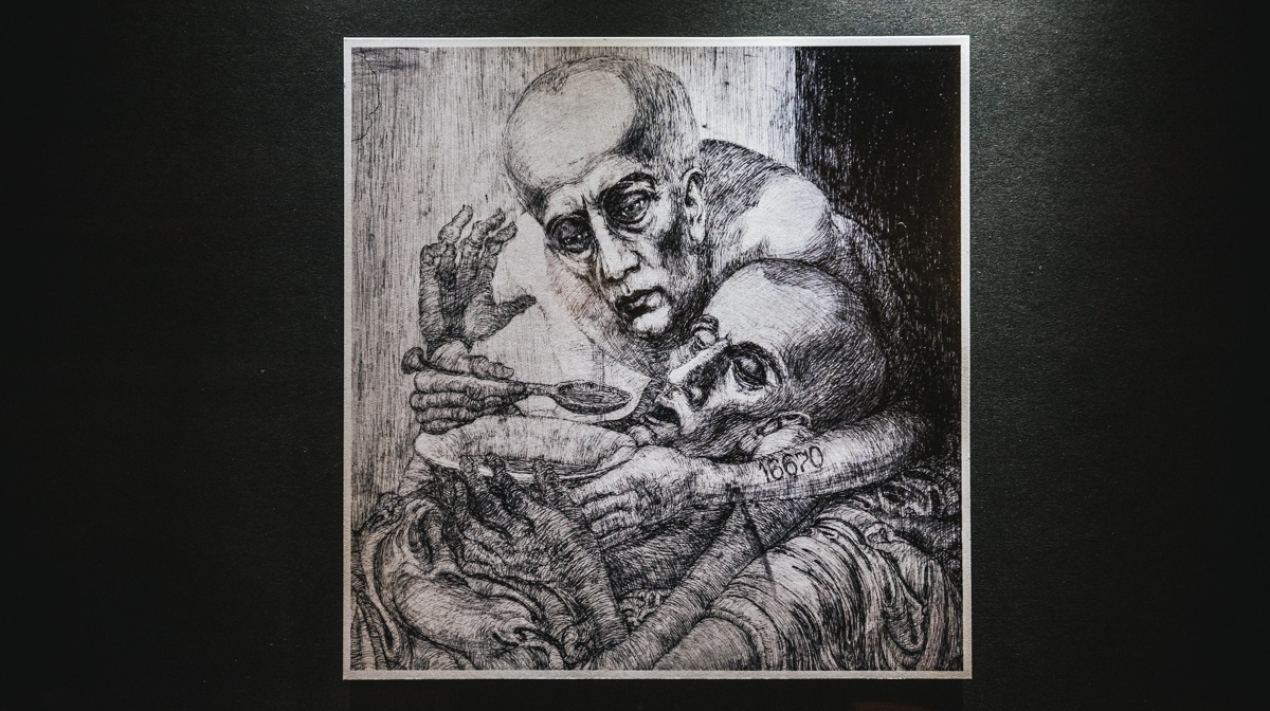

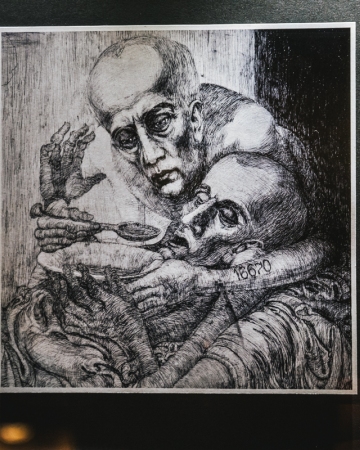

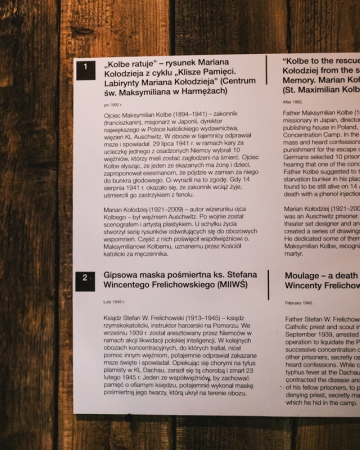

With the support of the Franciscan Order, the museum has displayed the drawing Kolbe Saves, created by artist and former Auschwitz inmate Marian Kołodziej, who shared imprisonment with Kolbe.

The drawing now appears in the concentration camp section, alongside a plaster death mask of Fr. Stefan Wincenty Frelichowski. According to Professor Rafał Wnuk, acting director of the museum;

This artifact allows us to tell the stories of those who defied the oppressive camp system, helping others rather than focusing solely on survival—a choice that often led to death. Father Kolbe stands as a symbol of sacrifice.

The artist, Marian Kołodziej, was among the first prisoners of Auschwitz in 1940, bearing the number 432. After the war, he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków and became a set designer for Gdańsk’s Wybrzeże Theatre, receiving honorary citizenship.

Later in life, Kołodziej created artwork inspired by his memories from Auschwitz, including a series titled Labyrinths of Memory, now on permanent display at the St. Maximilian Center in Harmęże.

He began this work in 1993, completing over 260 pieces before his death in 2009. According to Monika Krzencessa-Ropiak, Head of Exhibitions at the MSWW; “This powerful and haunting story is portrayed with the simplest artistic means.”

The museum provides context for the drawing, explaining how German concentration camps systematically stripped prisoners of their humanity. An inscription on display reads:

“[The Nazis] aimed to turn prisoners into a submissive mass, devoid of compassion. Those who chose to help strangers reduced their chances of survival, yet they bore witness to a defiance against the camp’s cruel logic. Some drew strength from their faith, others from different sources. Religious practices, banned by the SS, held particular importance for the faithful, and clergy from various denominations were especially respected for selflessly supporting fellow inmates. Sometimes, this came at the ultimate cost.”

The exhibit also includes a biography of Fr. Kolbe (1894–1941):

“...a Franciscan friar, missionary in Japan, director of Poland’s largest Catholic publishing house, and prisoner of Auschwitz. In secret, he celebrated Mass and heard confessions. On July 29th, 1941, after an inmate escaped, the Nazis selected 10 prisoners to starve to death. Hearing that one of the condemned had a wife and children, Kolbe offered himself in exchange. The SS agreed. When he was found alive on August 14th, 1941, he was executed with a phenol injection.”

The museum consulted with historians from the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum as well as Franciscan experts on the wording for this addition.

In the future, the museum plans to honor the Ulma family by displaying an artifact that once belonged to Józef Ulma.